Operation Overlord: Normandy

INTRODUCTION. For the people of occupied France dawn broke finally on Tuesday 6 June 1944, a date that will forever go down in the annals of military history as ‘D-Day’. On this day Allied powers of Britain, the United States and Canada finally launched their long anticipated cross-Channel attack against Hitler’s ‘Atlantic Wall’. Codenamed Overlord, this offensive along fifty-five miles oft he Normandy coastline was, and still is, the ‘greatest assault that has ever been made on a fortified and strongly defended coast by combined sea, land and air forces’.

The scale of this operation was colossal involving as it did 7,000 naval vessels, 11,000 aircraft and over 1,750,000 men. As the largest amphibious invasion in the history of warfare it has, unsurprisingly, become an iconic moment in the story of the Second World War. Measuring eight or nine on the Richter scale of historic global events, D-Day has registered itself in the collective historical consciences of numerous participating countries.

-D-Day Documents, Paul Winter

CAPTAIN EA OLMSTED SUMMARY. By this point, Captain Olmsted would have served nearly five years in the Canadian military. He was serving as a G-III Staff (Operations) Officer with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division: 9th infantry Brigade Headquarters. It is difficult to imagine what experiences he would have encountered while in England, and what his mindset was at this point, but it seems reasonable to assume he had begun to “settle“ into his military career by now.

It is very likely that he would have been billeted in Aldershot in the lead up to the invasion. Not only is Aldershot a British military hub, but it was a known location where many Canadian soldiers were located [REF]. A pocket bible my grandfather had in a suitcase included pictures of his parents and a name and address in Aldershot. It’s unclear what relationship he had with this family, but it seems likely that he wanted his belongings sent there if lost. In his letters home, he gives no indication of what is to come (as would be expected) but it’s interesting to note that he seemed more concerned with life at home (eg. figuring our whether or not to sell his car, dealing with a warranty on a watch he bought my grandmother, etc.).

This section details a variety of information related to Capt Olmsted including his unit marshalling area and loading area in Southampton onto headquarters ship HMS Hilary, the unit accounts of D Day as well as his own personal accounts prepared for Cornelius Ryan’s “The Longest Day” and used for his funeral.

An explanation of the roles and positions within a Division HQ’s in the field Division:

"G" Branch was under the Colonel GS (a Lieutenant-Colonel), who was responsible for policy, as directed by the Divisional Commander, and the co-ordination and general supervision of work of all branch of the Division Headquarters. A Colonel AQ was head of the combined "A" and "Q" staffs. An AA&QMG in the rank of Lieutenant Colonel was the assistant to the Colonel AQ. Under him were:

A GSO II, acting as deputy to the GSO I. He was responsible for the preparation of orders and instructions as directed by the GSO I; the general organization and working of the "G" office; detailing of duty officers at the Div HQ; coordinating arrangements for moving the Main HQ; details of movement by road in consultation with the DAAG and DAQMG; and general policy regarding HQ defence and the preparation and promulgation of HQ standing orders. (In an Armoured Division Headquarters, the GSO II was responsible for the Division Tactical HQ and the above duties were done by the GSO III (Operations).)

Captain Olmsted was a GSO III (Operations) Officer: effectively the understudy to the GSO II. He maintained the situation map; prepared situation reports; supervised the acknowledgment register; maintained the command matrix; prepared orders for the move of the Orders Group; and prepared orders for the move of the Division's Main HQ. The Canadian system was quite similar to the British System, because our Field forces worked in co-operation with British formations throughout the war.

Also noteworthy is the concept that there are two Divisional HQ’s when a Division is “in the Field. These are:

DIV MAIN: the main division HQ in which the Division Commander (a General) operated from

DIV REAR: the “second” division HQ’s in which the Division 2i/c operated from.

It is expected that Captain Olmsted could have been present at DIV MAIN or DIV REAR during different operations. However, this is important to understanding the role(s) he would have played while serving with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division HQ on prior to, on and after D-Day.

June 4. Southampton, UK.

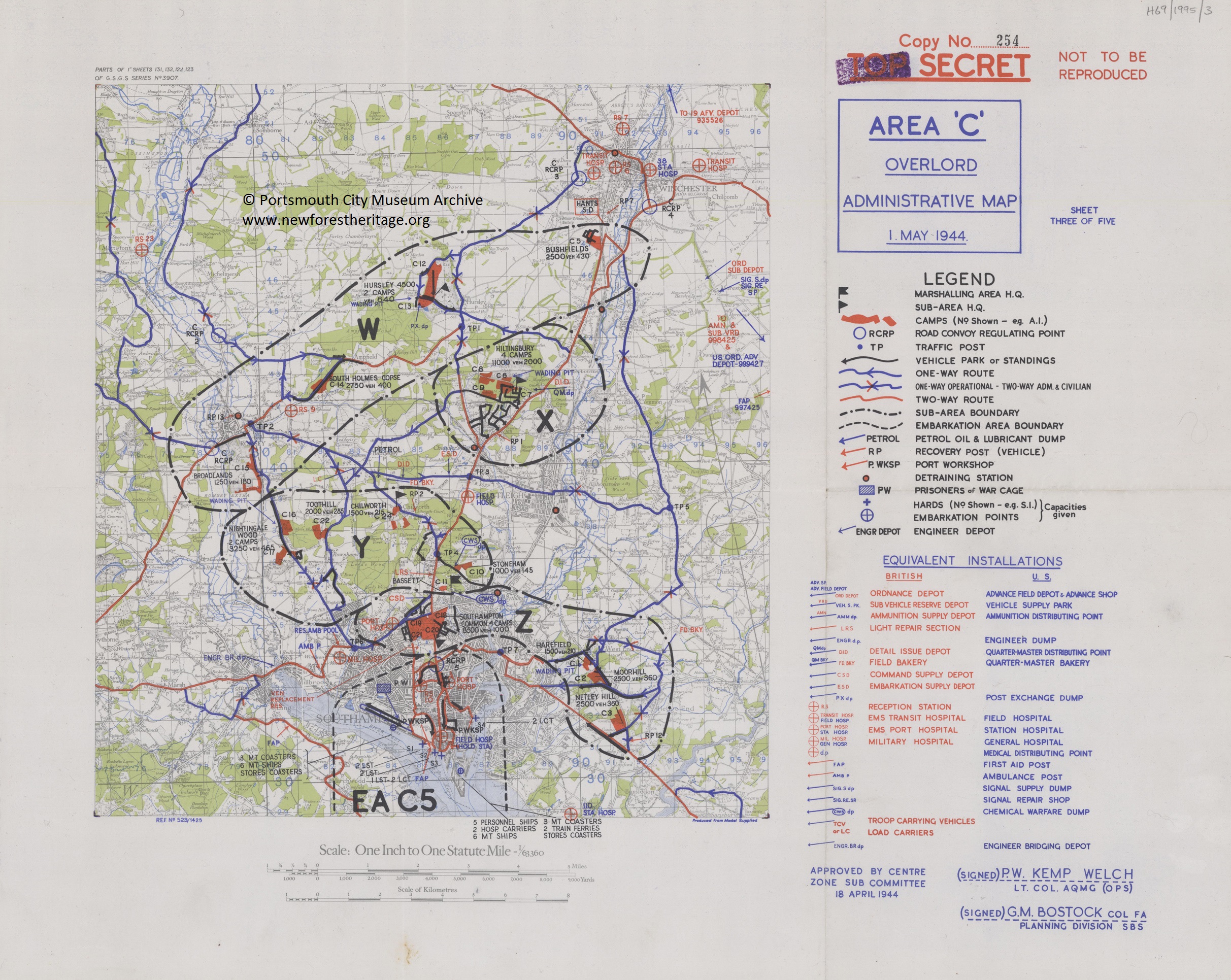

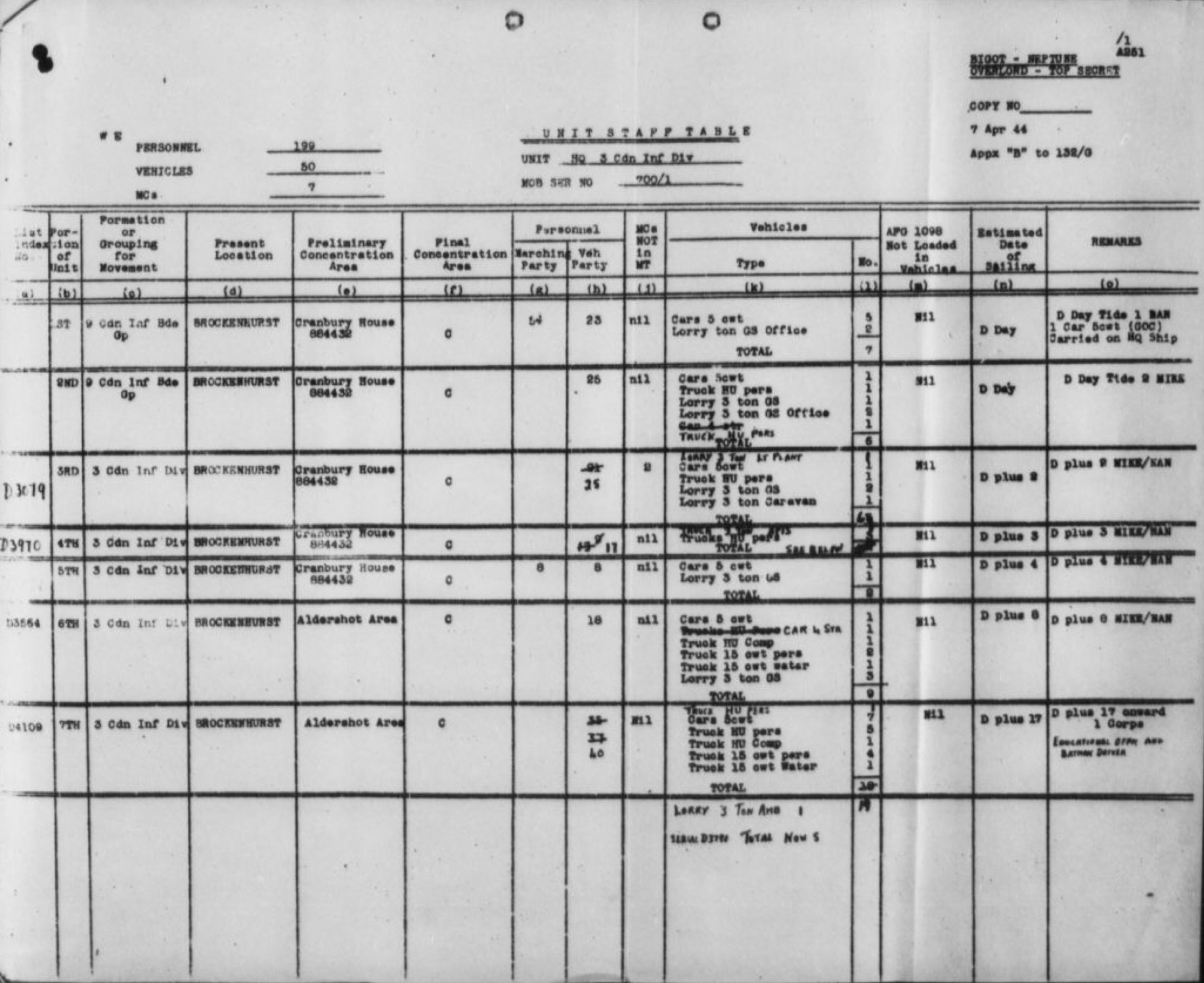

MARSHALLING AREAS. The marshalling area for the 3rd Canadian Division HQ (9th Infantry Brigade) has been identified as “Area C”, specifically Cranbury House Camps (C7). An associated map highlights Area 'B', specifically Brockenhurst, which is where Divisional Headquarters was located prior to being moved to Cranbury House. From here they made their way to their embarkation pier in Southampton Docks (EAC5) and eventually on to the headquarters ship HMS Hilary.

The map (right) highlights Cranbury street, which is a "y" between various highways just to the north of the Port. The troops could have walked from the camp to the docks - but it was pointed out by one supporting researcher that “officers rarely walk”. The troops were all taken from Southhampton Docks to the ship by tender (most likely from the ship’s landing craft assaults (LCA)). From loading, all ships then moved to their "anchoring" position, where they stayed until sailing.

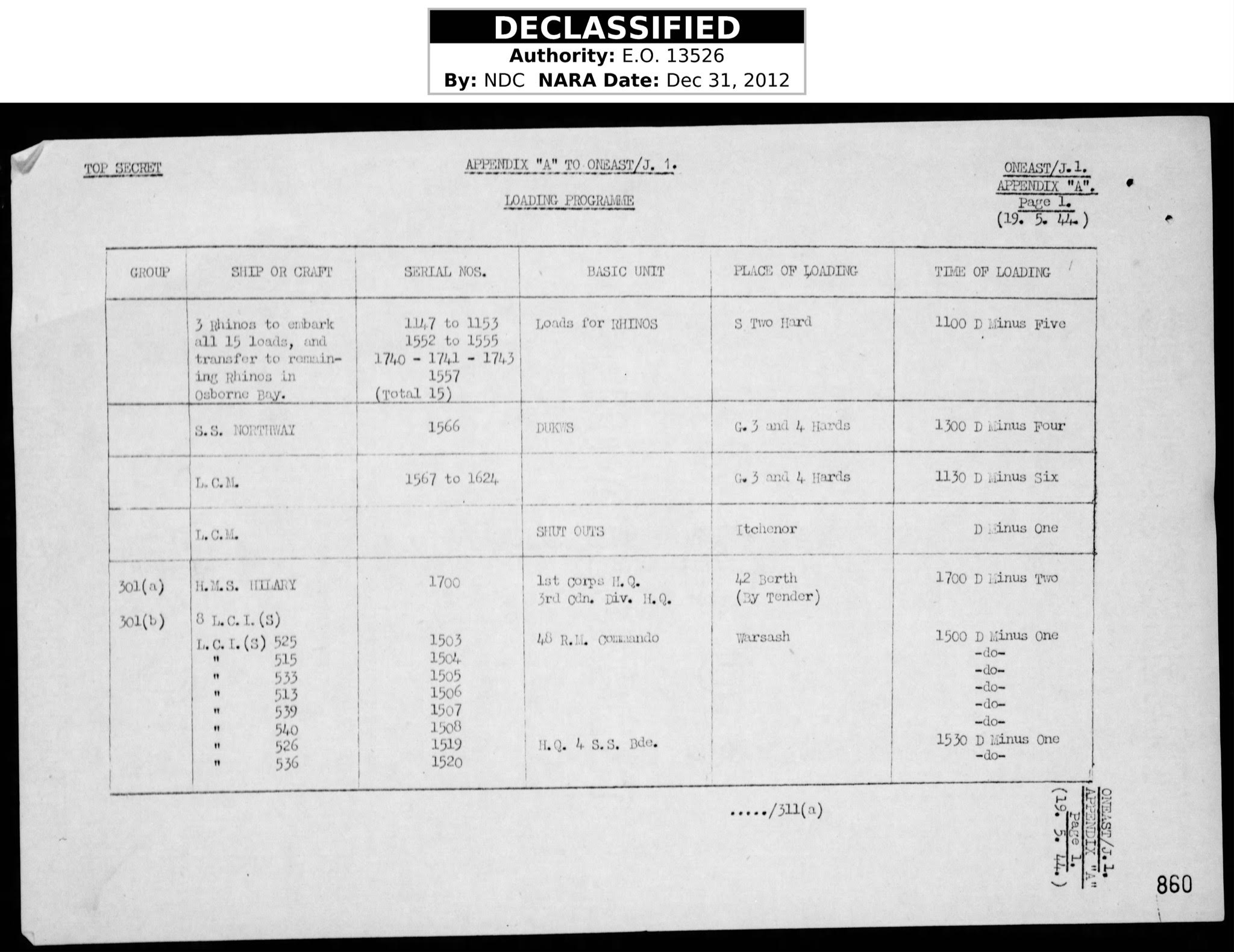

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division: 9th infantry Brigade Headquarters was part of ‘J’ Force (described further below). Loading plans and berthing plans are available, which indicate where each ship was berthed or anchored in the Southampton harbour. The loading plan is where each ship moved to load troops and equipment. When loaded it then would move back to its assigned anchoring position.

The Southampton Ocean Terminal (Eastern Docks) was used for docking larger ships during Operation Overlord, and was an embarkation point for personnel ships, hospital carriers, Motor Transport Ships, Motor Transport Coasters, Train Ferries and Stores Coasters. Southampton Town Quay was used for embarking troops who were camped in Marshalling Area C… From May 31 onwards, and according to a highly detailed timetable, troops began to make their way down to the coast and embark onto the ships and landing craft that would take them to Normandy. Vehicles were often loaded earlier, and troops on foot embarked only just before D-Day. The troops bound for landing on D-Day were followed by forces who would be landing on subsequent days, forming a steady stream moving down towards the south coast that in many places continued for months.

The unit war diaries suggest that at 19.25 they left Spithead Gate, having embarked troops while at anchor (Anchorage 19W/2) by tender from Southampton. On the Berthing Map, Anchorage 19/W is in the center of the map, 19W (2 likely meant the 2nd anchoring buoy). We know HMS Hilary was anchored at 42 Berth.

A modern map of the Southampton Port shows that Berth 42 is in the Eastern Dock area; Bert 42 Berth was located in the “Ocean Docks” part of the port.

June 5. Southampton, UK.

HQ 3 Cdn. Div. War Diary Entry [Southampton]. Weather: Dry, cool and strong wind. Today at 0900 hrs we received the signal for which we have been waiting – the signal to go. At 1100 hrs we pulled out of SOUTHAMPTON WATER to rendezvous at CALESHOT with thousands of other landing craft and ships, spreading out as far as the eye can see. The most amazing thing so far is that in spite of the collosal concentration of ships, troops and equipment, there has been no attempt by the Luftwaffe to bomb. The answer must be that RAF has gained complete air supremacy and the first round is ours.

At 1430 the convoy left anchor and we started off on our way to the coast of France. There is a strong wind and the sea is pretty rough for an LCT. Seasick tablets have been issued but in a number of instances fifty tablets would have made no difference. More than one man looks like death warmed up. Final messages from Montgomery, Eisenhower and Crerar were read to those who were able to listen and had their heads out of vomit bags. The Landing Tables, result of months of work, have stood up. We have every vehicle in its allotted place aboard the various craft - but anything else to be added would require a shoehorn.

-9th Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ War Diary; WO 179/2893; Captain G. E. Franklin for Brigadier-General D. G. Cunningham

HMS Hilary Ship Design plans (Imperial War museum)

HEADQUARTERS SHIP HMS HILARY. S.S. Hilary was a British civilian transport ship launched on 17 April 1931 for the benefit of the Booth Steamship Company. Comprising 80 first classes and 250 second classes, she is intended to carry passengers from the United Kingdom to South Africa. Required by the Royal Navy on October 16, 1940, which transformed it into a warship, she was named F22 HMS (Her Majesty Ship) Hilary. Carrying allied soldiers across the Atlantic, she was torpedoed in October 1942 but the torpedo did not explode. Re-armed the following year in a projection and command building, she participated in Operation Husky in Sicily in July 1943… She then took part in Operation Avalanche in Sicily, before joining Portsmouth in December 1943… Committed during Operation Neptune as the flagship of Force J, she led the convoy J11 to Juno Beach. Slightly damaged as a result of an air attack on 13 June, she replaces the HMS Scylla’s flagship, HMS Scylla, on 23 June, defeated by an underwater mine.

-Index of Allied warships during Operation Neptune

The following images show HMS Hilary at various stages. All pictures were sourced from the British Imperial War Museum.

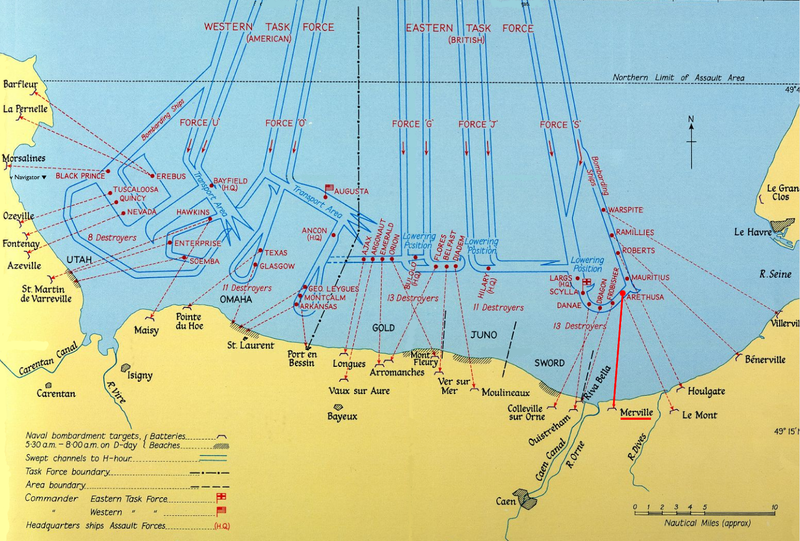

EASTERN TASK FORCE: FORCE J - CHANNEL 7. The Canadian forces were part of Force J; apart from the Flag Group these groups were destined for Mike Red and Nan Green beaches on Juno. HMS Hilary was part of Group 301 - Flag Group.

The various components of this group sailed from different mooring areas and rendezvoused at North Gate which they were timed to pass at H-12 Hours. The group was to sail at 9 knots. HMS Hilary, Flag Force ‘J’, carrying commanders Force ‘J’, I Corps and 3rd Canadian Infantry Division included:

• CMB 103, MTB 328 and MTB 344 joined from Cowes. CMB were early, small MTBs from WWI.

• MTB 328 broke down and was towed back to Portsmouth

• 8 x LCI(S) carrying Commandos joined from Hamble

• 2 x LCI(S) joined from Hamble. These were spare craft which could replace any becoming casualties before sailing. If not required for that role they were to be used for close protection for HMS Hilary and for picket duties

• USCGC, a rescue cutter joined from Ramble

• LCS(L)(2) 254, 255, 257. Joined from Cowes

• HMCS Algonquin (Escort)

Through this research it was identified that the grandfather of a close family friend (Sub-Lieut. Neil Henley Chapman) was aboard HMCS Algonquin on D-Day, meaning that he was on another ship in the Flag Group designated as an escort. HMCS Algonquin would later go on to play a pivotal role in not only the protection of Force J ships, but also in the close fire support of troops landing on Juno Beach.

June 6. Normandy, France.

9th CANADIAN INFANTRY BRIGADE. 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade was the Canadian force reserve brigade and had the task of passing through 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade and advancing to the final objective on the line Authis, Ardenne, Carpiquet. The brigade had been circling in its LCI(L)s and LCT's offshore for some two hours before it received the order to land.

Wrecked craft and congestion led to the decision to land all the brigade through Nan White… Once the brigade and its vehicles were ashore they then had to struggle through Bernieres which was still crowded with vehicles and personnel from 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade. The Divisional GOC held an ‘O’ Group and it was decided that 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade would advance as soon as Beny sur Mer was reported clear. The brigade had trained as a mobile brigade and was to advance as follows:

Stuart Light tanks of 27 Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment)

‘C’ Company North Nova Scotia Highlanders in the battalion Carrier Platoon.

One platoon of ‘C’ Company Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (machine gun).

One troop of M10 SP anti tank guns from 105th Canadian Anti Tank Battery, RCA

Two sections of the battalion Pioneer Platoon.

Four 6 pdr guns from the battalion Anti Tank Platoon.

The remaining three companies of North Nova Scotia Highlanders each carried on the tanks of a squadron of 27 Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment)

Stormont, Dundas and Glengary Highlanders and HLI of Canada each with three companies on airborne bicycles and on company carried in the battalion vehicles.

The vanguard advanced until ‘C’ Company met enemy opposition at Villons les Buissons. At the same time ‘A’ Company became involved in a fight at Colomby sur Thaon. It was decided to dig in for the night with North Nova Scotia Highlanders and 27 Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment) in the area of Villons les Buissons and Anisy. The other two battalions would remain in the Beny area. The brigade group had suffered some 30 casualties during the day.

It might appear that 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade had shown some lack of drive. However it had advanced further than the units on either flank and would have been dangerously exposed if it had continued.

Canadian Assaults on D Day; note direction of 9th Inf. Dif. reserve and corresponding location of nan white beach and

HQ 3 Cdn. Div. War Diary Entry [Normandy]. Weather: Cool, dry and a strong sea running. After an uneventful night it started to get light at 0345 hrs. 7 and 8 Bdes landed at 0730 hrs after the coast had received a terrific beating from RN ships, SP arty, rockets, hedgerows etc. Flotilla of this bde went round and round in a circle waiting in turn to land. COURSEULLES, BERNIERE and ST. AUBIN could all be seen and they were on fire in many places. A destroyer on our port hit a mine and the report came through that a cruiser astern had also been sunk. Very little fire coming from beaches out to sea from the enemy coast defence batteries.

The order to land the bde on Nan WHITE was received about 1030 hrs. No part could be landed on Nan RED as planned and all personnel and vehicles had to come in on the one beach and out through BERNIERE-SUR-MER. The bde got off the beaches quickly but there was a bad traffic jam in the town which took some time to untangle. Bde HQ suffered the first casualty on landing when Capt. Roy Gilman, BRASCO; was either killed or wounded and evacuated to England. Cpl. Kasper was the last to see him as he was riding across the beach on an M 10 SP A tk gun when a carrier in front went over a mine and nobody has seen him since…

After a halt of about an hour on the road Bde HQ moved forward and set up its first headquarters in France at BENY-SUR-MER and awaited orders from Division for the brigade to advance, pass through 8 Cdn Inf Bde and capture the airfield at CARPIQUET. 8 Bde had not been able to get forward as quickly as had been hoped having been held up at the radar station, TREVILLE and DOUVRES. 7 Bde, contrary to expectation, had found after landing the going easier than on the left and pushed forward quickly. The position of our first HQ was not long lived as we were in a wood which was apparently ranged for mortars as a few started dropping shortly after our arrival. By hrs all units had reported they were in assembly areas and ready for the word to go.

Nth NS Highrs and 27 Cdn Armd Regt led off at hrs followed by SD & G Highrs and by night Nth NS Highrs and the tanks were in the vicinity of the crossroads north of VILLONS LES BUISSONS under mortar fire and shelling. Bde HQ moved to field near church at BASLY. There was a good deal of sniping during the night by pro-boche personnel left behind during the enemy withdrawal. Strange as it may seem we must have attained surprise in the assault as we did not encounter any mines or booby traps back of the beach area and evidence that Gerry pulled out in a hurry is apparent when kit and equipment left in houses is examined. D-Day ended with all the brigade well established ashore and very few casualties incurred.

-9th Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ War Diary; WO 179/2893; Captain G. E. Franklin for Brigadier-General D. G. Cunningham

3RD CANADIAN INFANTRY DIVISION HEADQUARTERS

This unit was scheduled to landing under the control of 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade as serial 1700 Landing from Landing headquarters ship HMS Hilary and included:

Juno Beach - Canadian Assaults D-Day - Nan Beach

1 x car 5 cwt 4 x 4 (Jeep) with one crew from Headquarters I Corps. Command Group.

21 men from Headquarters I Corps. Command Group. Carried in a DUKW lowered from the davits of LSH HMS Hilary. To land at a time and on a beach at the Corps Commander’s discretion.

1 x car 5 cwt 4 x 4 (Jeep) with one crew from Headquarters 3rd Canadian InfantryDivision. Command Group.

21 men from Headquarters 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. Command Group. Carried in a DUKW lowered from the davits of LSH HMS Hilary. To land at a time and on a beach at the Division Commander’s discretion.

To land at a time and on a beach at the Division Commanders discretion.

Juno Beach Nan White Sector D Day Soldiers Marching

3 men from Headquarters CRA. Command Group.

3 men from Headquarters CRE. Command Group.

19 men from 3rd Canadian Infantry Division Signals. Command Group.

2 men from Headquarters 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade.

2 men. Principal Military Landing Officer and batman.

2 men. Commander 102 Beach Sub Area and batman.

2 DUKW with 6 crew from 297 GT Company.

4 men from Detachment ‘A’, Troop 3, Bombardment Unit Force ‘J’. Shore Bombardment Liaison Officer and party.

Nan White Beach

LCI(L)s land 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade. This brigade has the convenience of landing en masse as a unit. Transport lands half an hour later.

The above information provides context into the regiment’s (and Capt. EA Olmsted’s) planned landings. It is not known what specific group Capt. Olmsted reached Juno Beach with, but his personal account below also provides interesting context related to his landing party (which included a diverse group of senior Canadian personnel).

An important research question that is still under review is determining the specific LCA that Capt. Olmsted and his party would have landed in. The LCA’s from all ships landed their first assault troops, then went back to the ships and continue to transfer troops. Due to casualties (LCA’s destroyed in the first landings the LCA’s were assigned to go to whatever ship needed them to transfer troops at that time. It may be impossible to tell which specific LCA was used to transferred Divisional HQ’s personnel to the shore - but this is still being assessed.

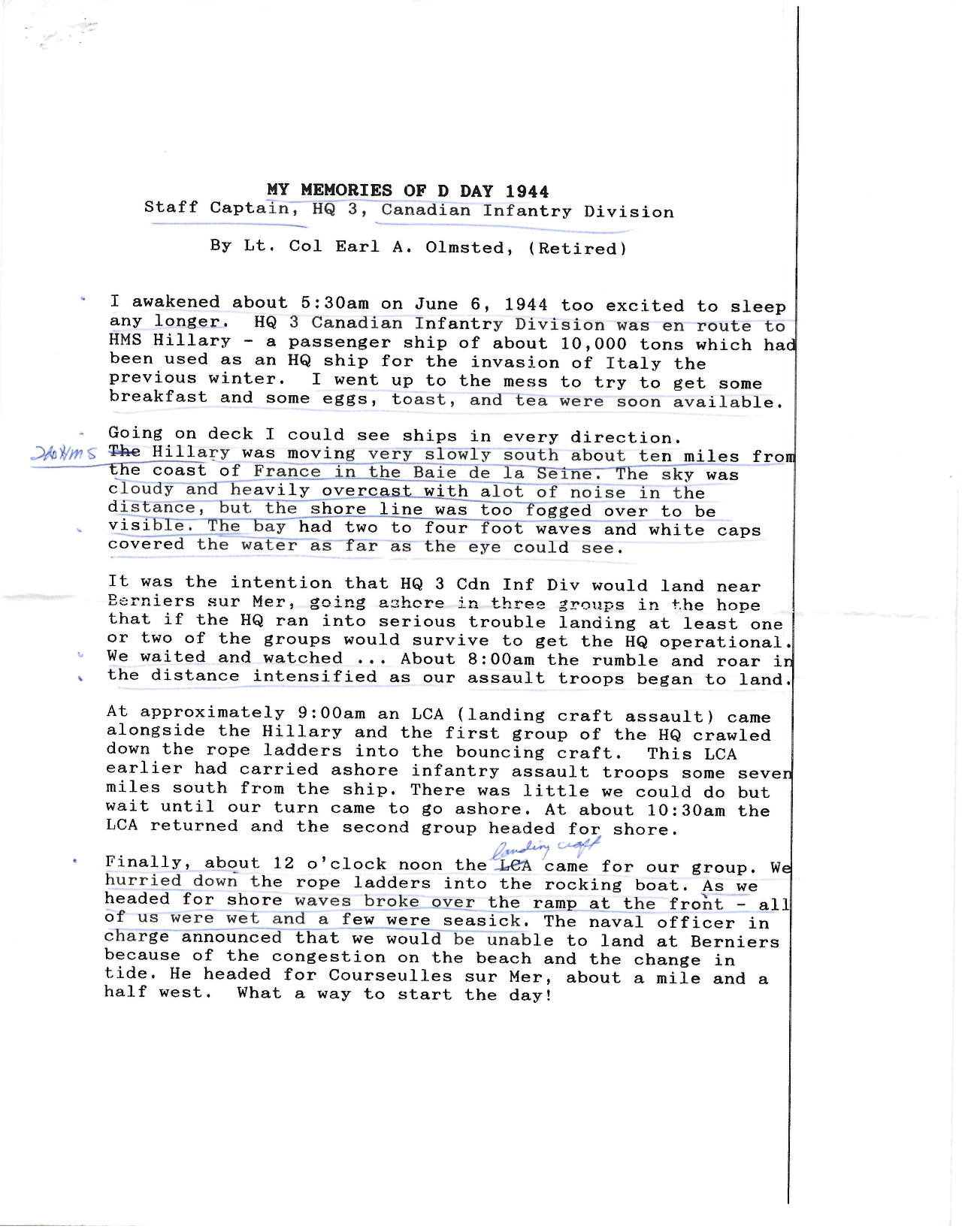

CAPTAIN EA OLMSTED PERSONAL D DAY ACCOUNT

I awakened about 5:30am on [June 6, 1944] too excited to sleep any longer. HQ 3 Canadian Infantry Division was en route to [Normandy aboard] HMS Hilary – a passenger ship of about 10,000 tons which had been used as an HQ ship for the invasion of Italy the previous winter. I went up to the mess to try and get some breakfast and some eggs.

Going on deck I could see ships in every direction. The Hilary was moving very slowly South about ten miles from the coast of France in the Baie de la Seine. The sky was cloudy and heavily overcast with a lot of noise in the distance, but the shore line was too fogged over to be visible. The bay had two to four foot waves and whitecaps covered the water as far as the eye could see.

It was the intention that HQ 3 [Canadian Infantry Division] would land near Berniers sur Mer, going ashore in three groups in the hope that if the HQ ran into serious trouble landing at least one or two of the groups would survive to get the HQ operational. We waited and watched… About 8Am the rumble and roar in the distance intensified as our assault troops began to land.

At approximately 9:00am an LCA (Landing Craft Assault) came alongside the Hilary and the first group of the HQ crawled down the rope ladders into the bouncing craft. This LCA earlier had carried ashore infantry assault troops some seven miles south from the ship. There was little we could do but wait until our turn came to go ashore. At about 10:30am the LCA returned and the second group headed for shore.

Finally, about 12 o’clock noon the LCA came for our group. We hurried down the rope ladders into the rocking boat. As we headed for shore waves broke over the ramp a the front – all of us were wet and a few were seasick. The naval officer in charge announced that we would be unable to land at Berniers because of the congestion on the beach and the change in tide. He headed for Courselles sur Mer, about a mile and a half West. What a way to start the day!

-E.A. Olmsted Part I of III

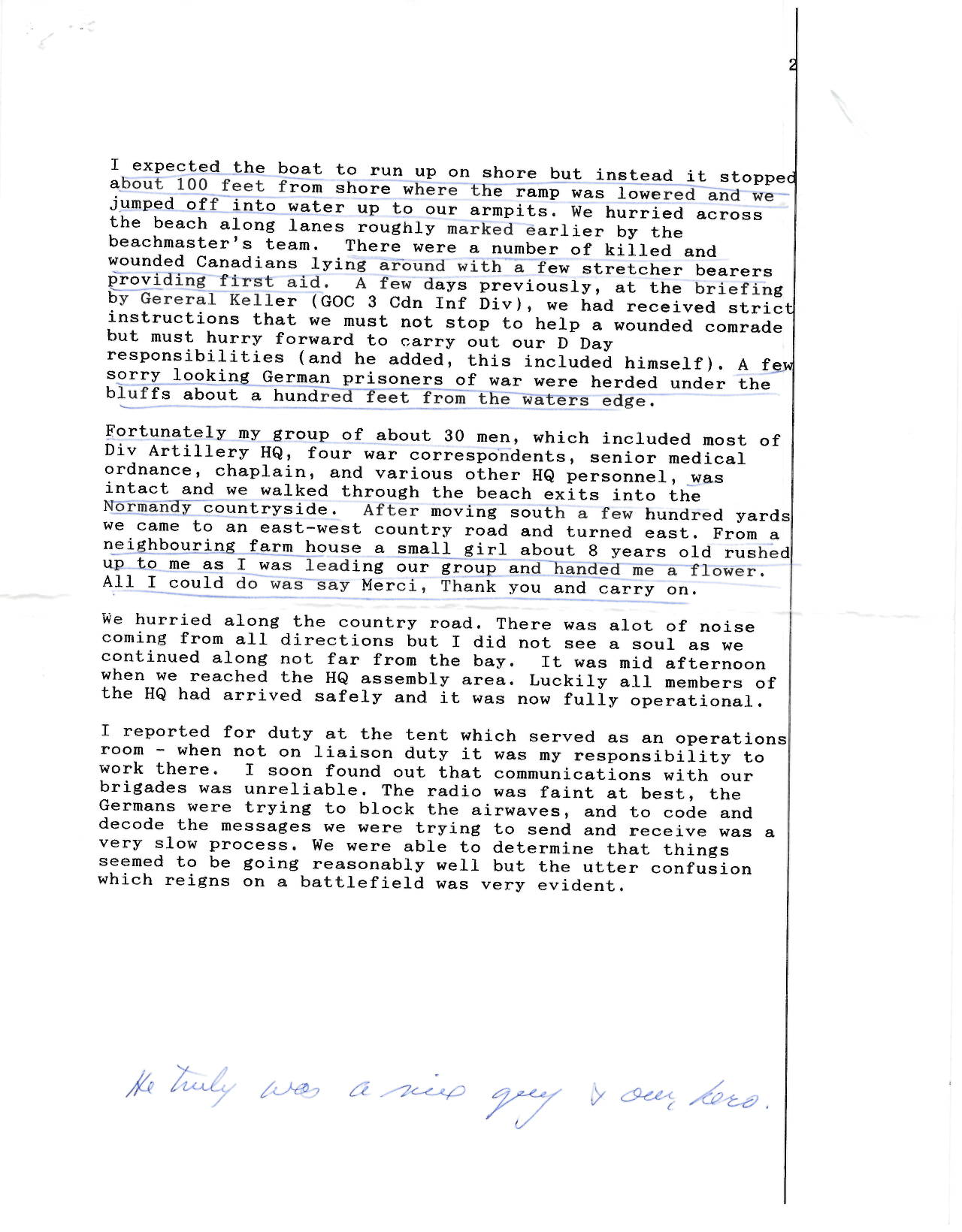

I expected the boat to run up on shore but instead it stopped about 100 feet from shore where the ramp was lowered and we jumped off into water up to our armpits. We hurried across the beach along the lanes roughly marked earlier by the beachmaster’s team. There were a number of killed and wounded Canadians lying around with a few stretcher bearers providing first aid. A few days previously, at the briefing by Genera R.F.L Keller (GOC 3 CDN Inf. Div.), we had received strict instructions that we must not stop to help a wounded comrade but must hurry forward to carry out our D Day responsibilities (and he added, this included himself). A few sorry looking German prisoners of war were herded under the bluffs about a hundred feet from the water’s edge.

Fortunately my group of about 30 men, which included most of Div. Artillery HQ, four war correspondents, senior medical ordinance, chaplain and various other HQ personnel, was intact and we walked through the beach exits into the Normandy countryside. After moving South a few hundred yards we came to an East-West country road and turned East. From a neighbouring farm house a small girl about 8 years old rushed up to me as I was leading our group and handed me a flower. All I could do was say Merci, thank you, and carry on.

We hurried along the country road. There was a lot of noise coming from all directions but I did not see a soul as we continued along not far from the bay. It was mid-afternoon when we reached the HQ assembly area. Luckily all members of the HQ had arrived safely and it was now operational.

I reported for duty at the tent which served as an operations room – when not on liaison duty it was my responsibility to work there. I soon found out that communications with our brigades was unreliable. The radio was faint at best, the Germans were trying to block the airwaves, and to code and decode the messages we were trying to send and receive was a very slow process. We were able to determine that things seemed to be going reasonably well but the utter confusion which reigns on a battlefield was very evident.

-E.A. Olmsted Part II of III

General Keller called me over and said he would like me to go up to 7 Brigade HQ and try to find out what was holding them up as he had not had any word of brigade progress for the past two hours. I checked the operation room map to determine the last reported location of the 7 Brigade and to ascertain the route I should take to get there. Then I looked around to find out what transportation was available. Fortunately a DUW (a large vehicle capable of travelling on both land and water) had brought in a couple of Famous James motor bikes. In England we had used Harleigh Davidsons and Nortons. The Famous James was a much smaller bike. It did not have a battery and had to be cranked to give the magneto enough electricity to get the motor started. I had never ridden a Famous James before but it presented no problems once I got it going.

Taking the road to Beny Sur Mer I proceeded South for a couple of miles. There were a few dead soldiers along the roadside and in the fields, most of them market by a rifle stuck in the ground with its butt up. Some of them were Canadian, others German. I could hear rifle and machine gun fire from several directions but no signs of life anywhere. Just North of Beny I turned West towards Rivers and then Southwest on to Colombiers Sur Selles, about five miles away.

As I rode along, near Colombiers, I saw Brig. Foster, Commander of 7 Brigade, and a few of his officers standing at the doorway of a house along the road. After a few words of greeting I conveyed the General’s message. Brig. Foster took me by the arm to the side of the house and pointed in three directions, explaining that the enemy were to his east and west and that his battalion (the Canadian Scottish) South of us, were facing heavy resistance and were in danger of being cut off. The Winnipegs to the west had not been able to make as much progress and had not yet joined up with the British division to their right. On his eastern flank 9 Brigade, having run into serious delays on the beaches, had not been able to move as far forward as 7 Brigade and there was an area three or four miles wide still in enemy hands. Later I realized that this was the area I had just ridden through!

-E.A. Olmsted Part III of III

In my grandfather’s account he highlights that he was with [four] war correspondents. This in opportunity for continued research as all of the correspondents below are considered persons of interest. Specifically, I believe Ross Munro and Charles Lynch were friends with my grandfather after the war. Reports from CBC indicate that Mathew Halton (an experienced war reporter) was one of nine correspondents who went ashore with the Canadians on D-Day…

Among the other reporters accompanying Canadian troops ashore on D-Day were Ross Munro and William Stewart for the Canadian Press, Ralph Allen of the Globe and Mail, Charles Lynch of Reuters, and Marcel Ouimet for Radio-Canada, CBC's French-language service.

In a famous clip, Halton says: "I've been up the beaches that one had dreaded so long, and seen this great event in history." Halton went ashore at the village of Graye-sur-Mer with Charles Lynch and a conducting officer. They spent the night in a French farmhouse and met the other reporters the next day to set up a press camp at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

GENERAL R.F.L. KELLER & BRIGADIER HARRY WICKWIRE FOSTER

General Keller is referenced several times by my grandfather in his personal accounts. He was the most senior Canadian Officer on Juno Beach and from what I understand was well respected by my grandfather. He is an important person of interest as he was in close quarters with my grandfather at several points on D-Day (namely aboard HMS Hilary and at the orchard where 3 Cdn. Div. HQ was established). He specifically ordered my grandfather forward from HQ to locate 7th Brigade on D Day. Information related to General Keller's presence on D-Day offers important clues as to my grandfather’s whereabouts.

Similarly, Brigadier H.W. Foster is a person of great interest, given he was commanding 7th Brigade. My grandfather’s account indicates that he was able to locate H.W. Foster at a house just inland and they had an interesting exchange (namely H.W. Foster seemingly frustrated that General Keller sought information as to his “hold up” due to significant German resistance in the area). At the time of writing, a relative of H.W. Foster has been in contact and is supporting these research efforts.

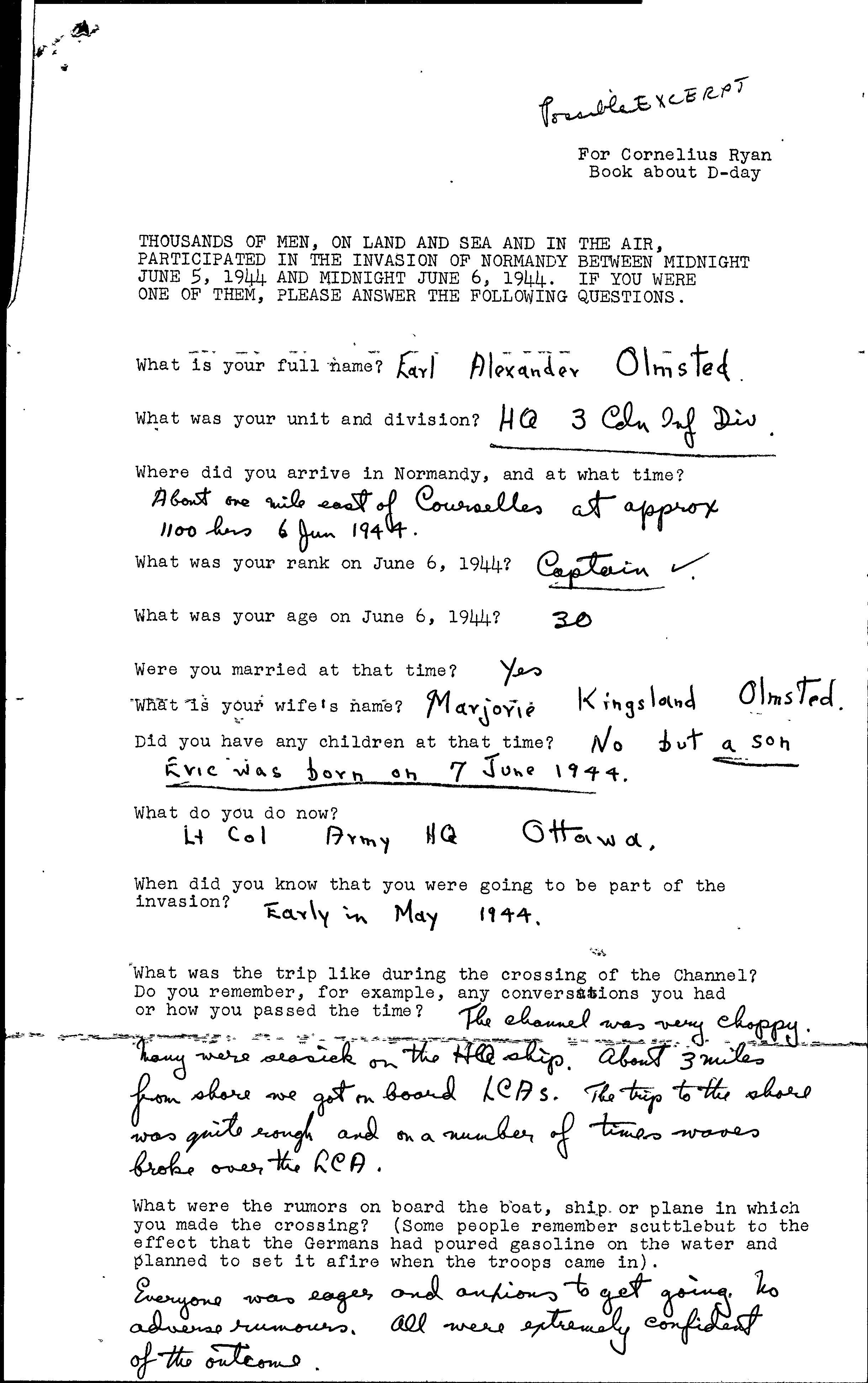

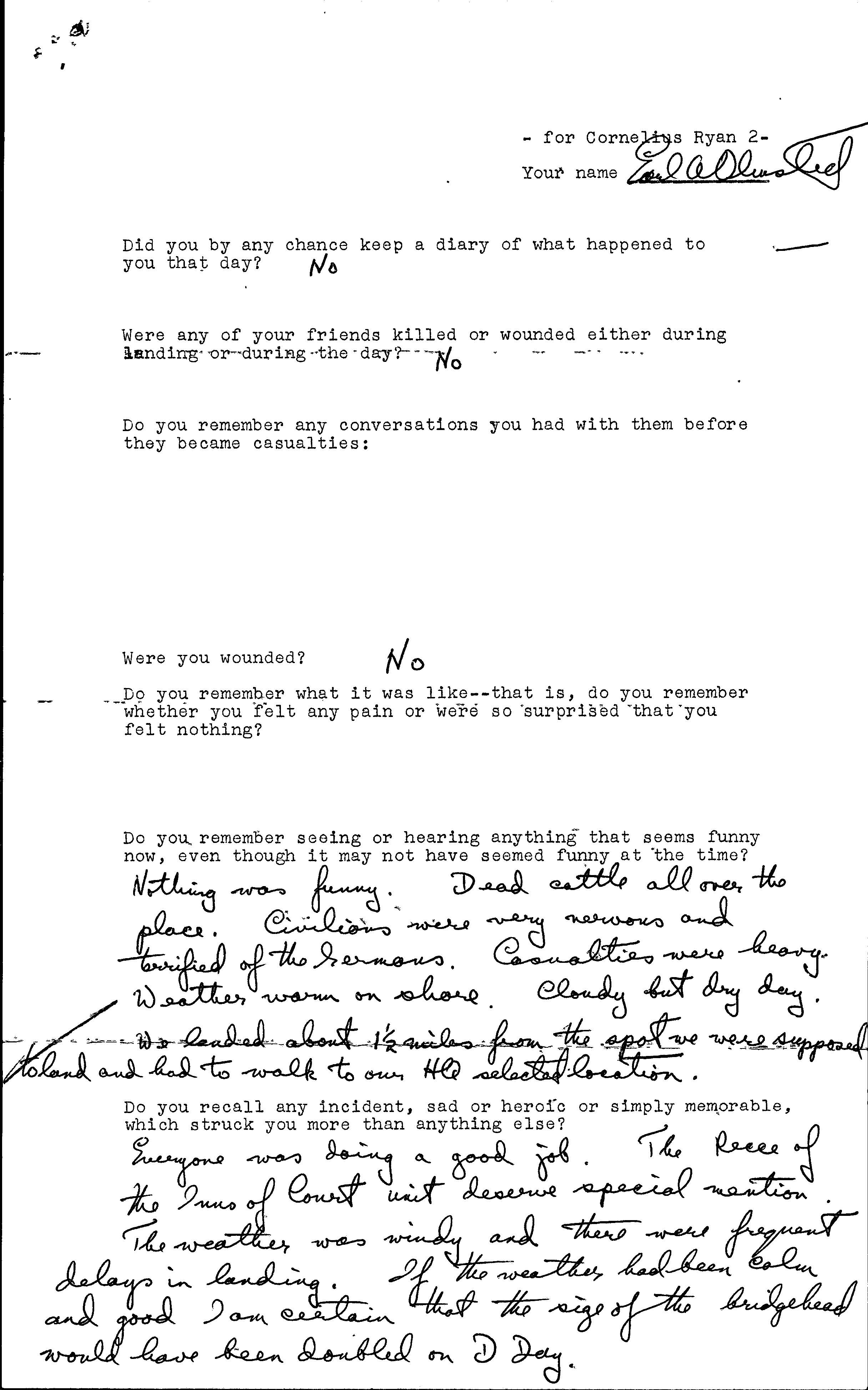

After the war, my grandfather wrote the following account of his D Day experience for Cornelius Ryan’s book, “The Longest Day“, which corroborates mush of the previous information that research has yielded. His personal account sheds interesting insight into his perspective on D Day - namely what appears to be a very calm and composed regimental headquarters.

Personal Diary Accounts - June 3 - 12

UVP has located the original handwritten diary accounts of E. A. Olmsted from Normandy. These accounts are currently being transcribed, but shed incredible light on the emotional state of the soldiers on D-Day and include a variety of interesting personal anecdotes that help to paint a more human picture of what these soldiers went through.

June 7. Normandy, France.

HQ 3 Cdn. Div. War Diary Entry [Basly]. Weather: Dry and sunny and the wind has dropped. [This has been a critical day with the brigade attacking, being counter attacked, and consolidating. A long, tiring and exacting day which ended with us further inland than any other British, Canadian or American troops except 7 Cdn Inf Bde who are even with us and going great guns.] During the night L Sec Sigs had their first casualties when the line party of Sgt. V.R. Whittingham and Sigmn Cook and Johnston went out to lay line and did not return. Their jeep was found later and it is presumed that they are prisoners. Bde HQ this morning captured more prisoners of war than probably any HQ since the beginning of time. It was not through any wonderful tactical move on the part of HQ but due to the fact that our position on the line of withdrawal of enemy who had been holding out at TAILLEVILLE overnight and as they came scurrying back we roped them in and put them in a cage at the church in BASLY. The PWs did not have much fight left in them and were ready to give up. There were a lot of foreigners mixed up in them. Cpl. D. Todd, BRASCO Cpl, did particularly good work going out by himself…

-9th Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ War Diary; WO 179/2893; Captain G. E. Franklin for Brigadier-General D. G. Cunningham